- Courting Context

- Posts

- The Context of Enough

The Context of Enough

A bit more than not quite, but rather less than too much.

How do you know when you’ve had enough?

Does something internal signal satisfaction?

Or is it something external — perhaps someone saying no, or go on, keep going?

How do you know? How can you tell? What might your definition depend on?

It’s already tough to discern what is “enough” when it comes to material contexts, like nutrition or movement. Not only does the definition of “enough” change with every scientific advance and study, but our ability to translate our bodily signals can vary dramatically per person throughout time making it difficult to pinpoint with the same kind of confidence we ascribe to a word like “more” or “less.”

“Enough” can serve as a warning, a plea, a zen koan to roll over in the mind when we periodically reconcile our inventory of present abundance against the predatory hunger of desire, temptation, and want. Not enough feels very different than almost enough, just enough, or even enough, already.

The very versatility of the word can backfire as vagueness. But at its best, there is wisdom in wielding this word, a judgment harmonizing something in the Self with a larger situational context. It is a word that both reads the room and speaks from personally calibrated sensitivity.

Which is why I haven’t been able to stop thinking about this:

That is quite the leap in one measure of “enough.”

Sure, it’s a smaller survey (and we all know how easy those are to manipulate in either direction), but Gen Z calls $587,800 — per year — as the new financial benchmark for success. That’s nine times the national average, according to the Social Security Administration. Roughly 3-6x what any other age group said they would need.

Yet 71% of Gen Z respondents said they expected to achieve financial success in their lifetimes, more than any other age group. Despite the fact that in 2022 over a third of people ages 18 - 24 reported no wage or salary income (vs less than a quarter back in 1990).

The statistics underscore the reality that $587,800 is an uncommon annual salary yet Gen Z are more confident about hitting that mark than any of the rest of us achieving our much more modest salary benchmarks. Rebecca Rickert, communications head for the financial firm that did the survey, summed it up thus: “Americans believe success is about self-determination not a pre-determination — which is quite powerful.”

Powerful enough to even obscure and overshadow the reality of the web of non-individuated contexts that also shape what we call “success?”

Because on the far other end of that uncommon income spectrum, the day-to-day financial reality of being homeless — to say nothing of the mental and emotional calculus of masking and guarding and maintaining vigilance — is statistically more likely to happen in life. Especially if you already know how much more expensive it is to live with a chronic illness or disability, like some are discovering with long covid.

Most of us are conditioned to look away and past unhoused people and their dogs in real life as we move throughout downtowns, like the author notes. But online, stories like the one above with no product to sell (besides a “brand” that I’m sure data analysts could describe in gruesome, cold, demographic-targeting precision), not even a platform tier or standalone course, simply can’t compete with the increasingly infinite (and financially backed) sources and streams and snackable hits of chronic content competing for our valuable attention, optimized to inspire, educate, delight.

If you haven’t already been grieving the loss of your attention (or at least the way you remember it being), understand that the value has spawned a dedicated economy so lucrative that most of Gen Z — and increasing amounts of every other generation — are seeking their fortunes online as content creators, influencers, and brand evangelists.

A lot of people have sort of given up hope on any kind of traditional career — why go work for someone else, when they’re going to exploit you or fire you tomorrow? They’re trying to make it on the internet, because it’s a huge lottery — if you can make it big, you can be really successful and rich.

How huge? As of April 2023 Goldman Sachs clocked the creator economy at $250 billion, with a forecast all the way to $480 billion by 2027. That’s quite the market share. So who’s really being delulu here? Gen Z and their aspirations of half-million annual salaries?

Or, as they might put it, are we the dumb suckers who keep buying into the exhausted illusion that career ladder loyalty will pay off in the end?

When brand deals are the main source of a Creator’s revenue at about 70%, and only 4% of global creators are deemed professionals (meaning they pull in more than $100,000 a year) — the numbers aren’t quite adding up to what some are expecting the gig to rake in. Even “started own brand” is less lucrative than “ad share” and only a little more than “affiliate links” or “courses” which ranks with “no income,” “tips,” and “other.”

This new economy starts to look a lot like the ones we think we’re leapfrogging, still asymmetrically concentrated across big brand deals, as a brand ambassador, or a brand evangelist. And these have rarely been long-time gigs. Contracts, mostly.

Today, the feeds are already full of so much self-promotion it’s become pedestrian, background noise. But if Sachs is anywhere close with their prediction of the creator economy doubling in size over the next five years, especially as AI gets closer to cranking out passable content at the speed and scale of growth/performance marketing dreams, it’s reasonable to expect our future feeds to feature even more influencers trying to influence us even more, even harder.

If you are going to follow an influencer, how can you make sure you’re selecting with care and choosing for quality? Heck — if you’re a content creator, as most of us increasingly have become, how ethical is it to lease your authenticity out to big brands paying top dollar? What are your ethical parameters?

Chances are, you might be a lot more vulnerable to cultish influence than you realize. Especially if you’re American.

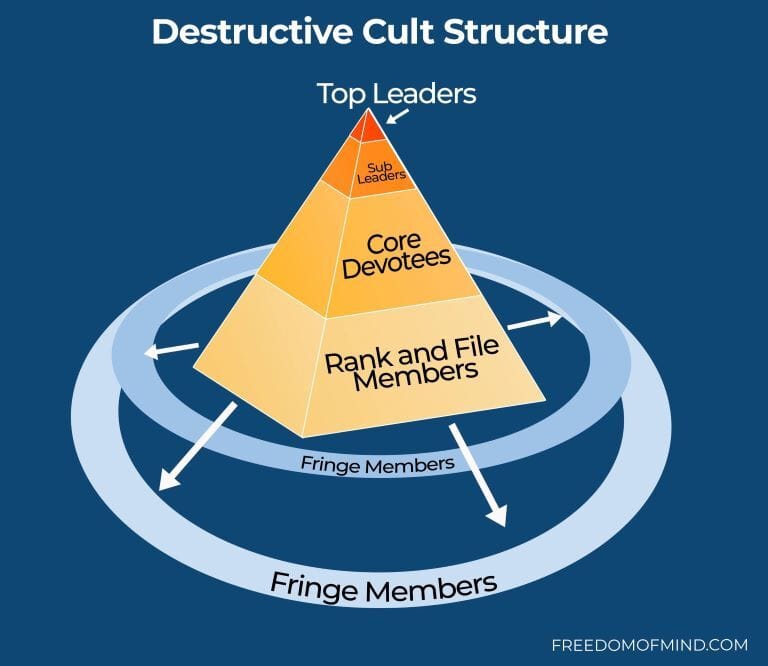

How would you know if you were in a cult?

It’s easy to call out a cult when we’re Othering, but when it comes to our own preferences we seem to be far more reluctant to call our own ties with groups, movements, or something larger (like “tech”) a cult. And that feels dangerous and reckless, especially in a country that financially incentivizes religious institutions by certain metrics that anyone can perform to a passing degree for the sake of tax avoidance, limitless income, and the promising projections that come with deeply loyal subscribers offering monthly tithes at varying levels of increasing volume.

Not only are Americans culturally (pun?) unprepared to guard against cults, we are mentally and physically disadvantaged. The pandemic worsened already difficult access to regular, quality mental and physical healthcare with a higher cost and barrier of entry than paying for a session or subscription with someone whose pitch is more persuasive in promising to heal what hurts us while pushing us towards prosperity.

So now seems like the perfect time to shore up defenses: the mental filters and gauges we use to keep an open mind, but not so open one’s brain falls out, as the saying goes. How do we follow the synchronicities of our own curiosity while avoiding algorithmic traps and rabbit holes fast-tracking radicalization in every direction?

As needs must, cults continue to evolve, today comprising a full spectrum catering to the reddest of pills and the thinnest of blue lines, to pastel QAnon and Akashic star seeds from yogaworld.

How can we guard against cultish influence?

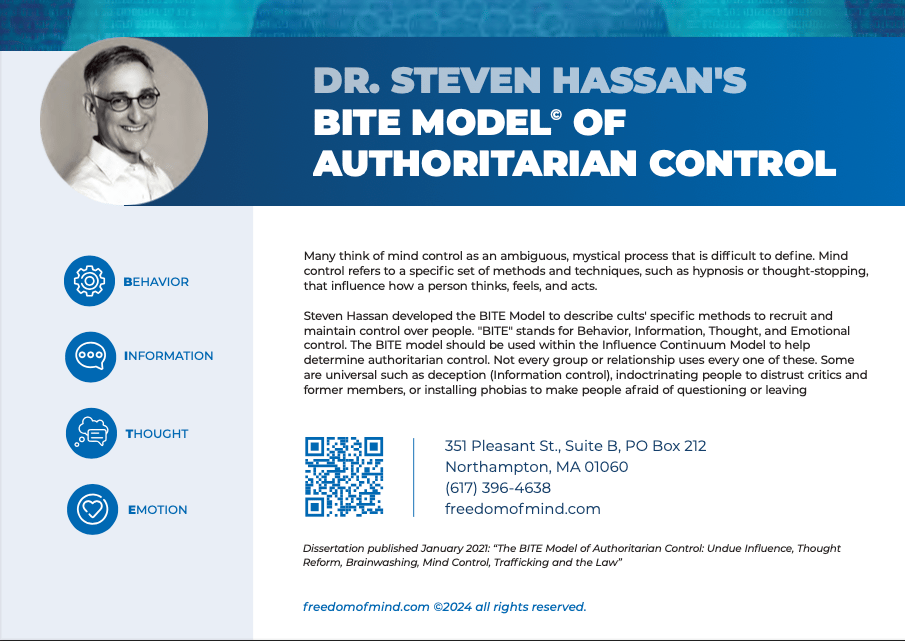

How much do we know about cults, anyway? Who would we consult to advise sensibly on this topic? Maybe a self-professed ex-Moonie like Dr. Steven Hassan, whose deep brainwashing as a Unification Church recruiter was interrupted only after a life-threatening car crash and intensive week-long intervention? He since went on to acquire formal degrees and publish peer-reviewed work to establish a better body of academic research and practice to promote awareness of and resistance to coercive control, mind manipulation like brainwashing, and undue influence.

Sounds objectively credible, a good place to start, right?

From his website freedomofmind.com (but I grabbed the locked PDF in full, below)

|

Rather a handy file to have on hand should you want to teach an AI how to be a better content curator, editor, or sentinel: dear Siri, filter all my social and RSS feeds through this BITE model and Influence Continuum. Let me know which sources are trending Destructive/Unhealthy and show me examples of how. Give me better sources that meet Constructive/Healthy guidelines, and exhibit low or occasional usage of behavior control, information control, thought control, and emotion control techniques.

What else might we add, to describe the harmful influences we hope to guard against?

What would our feeds look like, laundered through this lens? (Would there be any sane crypto commentary at all were it not for Molly White?)

Where else might we find these kinds of patterns across history, and life today?

When does the promise of tech start to sound more like predatory, and alarmingly zealous while we’re mentioning it?

When do warranted accolades and genuine admiration curdle into toxic adulation?

What happens when user adoption engagement strategies start to sound uncomfortably close to the trauma-bonding techniques found in groups and interpersonal relationships rife with abuse?

Where does cultish language, behavior, thinking, and practice show up in our life when we know what to look for? Has it become so commonplace it longer stands out?

Something like a familiar formula, more funny than fearsome?

Charisma doesn’t always have to be intense.

Who and what, then, can you trust as authorities, guides, coaches, consultants, planners, allies, and partners to protect you from the crush of undue influence?

Dr. Hassan says in several of his lectures online that nobody ever joins a cult: they are recruited, and usually under loads of deception and false pretenses. This is just as much to inspire empathy for unfortunate others as it is to be a wake-up call for us, too. The fringe has now become so mainstream it’s getting federally installed in the new administration. Less regulation on this stuff overall means we have to focus more on self-regulation, or co-regulation. But we’re gonna need better boundaries.

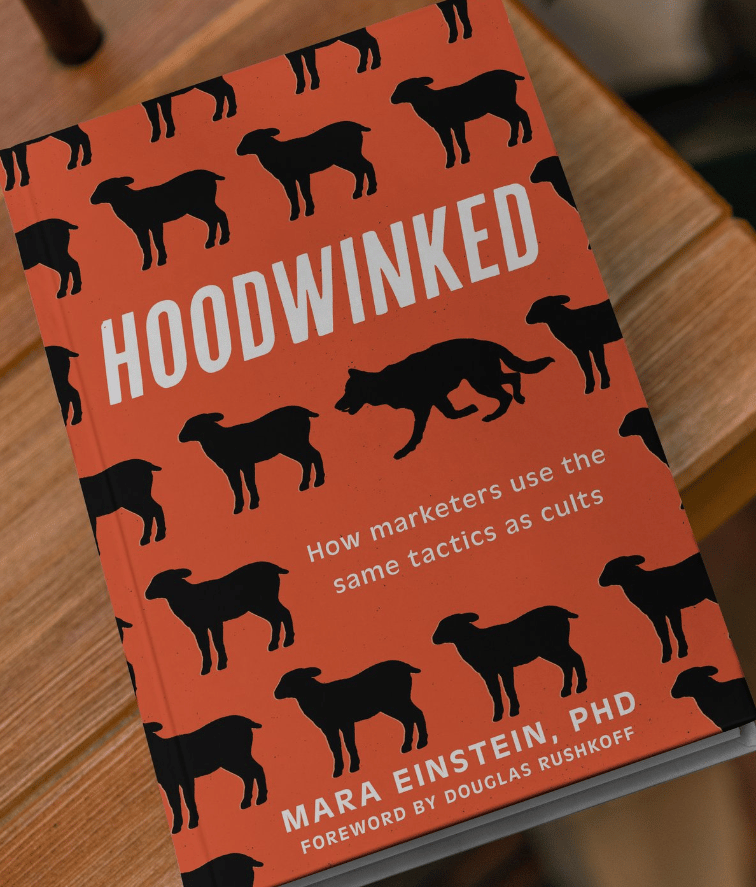

Because if you thought I was using cults as some kind of hyperbolic metaphor, here’s how the sizzle page for the upcoming Hoodwinked by Mara Epstein puts it:

Companies have discovered that consumers can be lured by sophisticated and deceptive marketing techniques, like sensory marketing, cult branding, influencers, and AI programmed to induce maximum anxiety. Combined with behavior-modifying apps and persuasively designed UX that compels us to buy things we don’t need or cannot afford, goods and services like prestige education, fitness trackers, makeup, and those viral leggings from American Eagle seem like must-haves rather than luxury extras.

Aided by algorithms and buoyed by the greed of social media CEOs, marketers use the same deceptive and emotionally manipulative tactics that cults do, including scarcity, an all-encompassing ideology, and a charismatic leader. Once indoctrinated, consumer-followers become ensnared in the perfect capitalist loop: anxiety-purchase-anxiety-purchase-anxiety-purchase. Then, social media appearances reinforce the cycle of purchase, performance, and panic.

Using memorable real-life cautionary tales, Dr. Einstein narrates how smart, sensible people are sucked into the cult marketing vortex and, importantly, what enables them to get out. Protection comes from understanding the scope of the problem and knowing how to spot the many pervasive tactics used.

How can we stay kind and curious as you explore contexts in constant flux? Can we let today’s enough look different than someone else’s, or our own from a different time?

What would we need to do to learn how to hear our own true heart’s desires again, and trace the roots of its rhythms? To reconnect with families, communities, and histories to honor and call upon the guardians and protectors we depend on, because none of us ever does any of this completely on our own?

As the year comes to a close, what are some ways we could try to take time to disconnect, get some distance, and gain some slow perspective around the shape of our enough, in the many ways it shows up in our life?

What does it feel like somatically, within the body to hover between lack and satisfaction and waste? When enough is nearly in reach, or left in the dust?

What helps to tune into those signals? Do they register best in moment of stillness, silence, a bit of both, or emphatically in other directions?

Where can our curiosities lead us when we react less to the influence of others and more in service of our deepest, truest dreams?

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25771420/247400_AI_friend_CVirginia.jpg)